FROULJU FAN FRYSLÂN

women of Friesland, eight portraits in bronze and movie Culture capital Leeuwarden/Fryslân 2018

in collaboration with documentarymaker Marleen Godlieb and Omrop Fryslân

Film:

https://vimeo.com/219837406/63b4404857

FROULJU FAN FRYSLÂN,

a film about the making of the hall of fame of the Frisian women by Natasja Bennink

The documentary on NPO 2/FryslanDOk:

www.npostart.nl/fryslan-dok

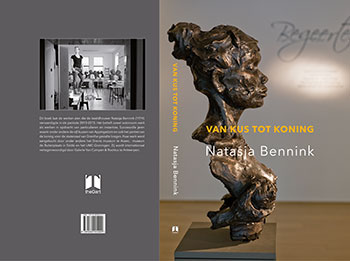

FROM KISS TO KING

Bronzes Natasja Bennink 2010-2015

photography: Reyer Boxem

text: Harry Tupan, Drents Museum

Publisher: TheoArt, Groningen NL

ISBN 978-90-809050-0-09

translated into English and German

The book is available:

Art Gallery Van Campen & Rochtus, Antwerp Belgium

Bookshop Van der Velde, Groningen NL

or send a email to:

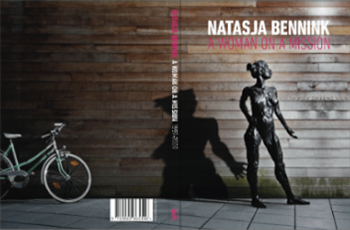

A WOMAN ON A MISSION

beelden Natasja Bennink 1999-2009

concept+vormgeving: Rudo Menge

fotografie: Reyer Boxem

beschouwing: Roos Wouters

gedichten: Maria van Daalen

Uitgever Galerie VCR, Antwerpen en BAI, Scholten

ISBN 9789085865346

Het boek is verkrijgbaar bij:

Galerie Van Campen & Rochtus, Antwerpen

tel +32(0)3 2940662

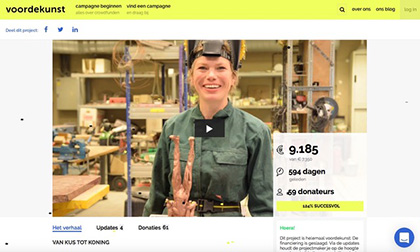

Compilation of the documentary: De 5 kussen

Marleen Godlieb, stichting Noordgedacht. 2013

Artist in residence, Radio NPO 4, Opium.

Natasja works a week in the tower-room of VondelCS, Amsterdam :

Studioview: the Five kisses of Appingedam in progress, 2014

Former city hall of Ezinge, NL, now house and studio from

Onno Broeksma en Natasja Bennink on TV by:

KRO Binnenste Buiten NPO 2::

https://binnenstebuiten.kro-ncrv.nl

My goal is to create statues that communicate, with universal, socially engaged content. Providing that physical experience in a field of meaning, recognition that provoke at the same time. My work mainly consists of life-size sculptures in which the human body is used as the bearer of meaning: man as allegory.

For me, the corporal provides a frame of reference to show in what way the personal is intertwined with the social and vice versa;

The dialogue between the users of the public area; their personal reality and the cultural, social topicality in relation to my work.

One of the themes I work with is the position/depiction of women, balancing on the intersection of art and society.

Throughout all of Art History, many Venus statues have been created and women have been depicted in many ways. Nowadays, women are both cliché and iconic in the rapid visual culture. ‘My’ Venus statues are an ode to today’s and tomorrow’s women, very recognizable to modern man with a hint of girl power.

Due to the roughness and the reduction of the anatomy of the model to the main lines and shapes, an image is formed that is incomplete, but, due to gaps and holes invokes a tension that transcends the model. During the work process, the work enters several stages. The starting point always is human anatomy, in which the actual presence of the model is essential. The human body acts as translation of the concept.

I translate the place of man as an individual in the tension between personality development / self-glorification mainly by using my own body as a basis.

Natasja Bennink – With a rough edge

Harry Tupan

This book exhibits the work of Natasja Bennink (1974), sculptor of monumental statues in bronze. It is a retrospective of her sculpture over the last five years: From Kiss to King. I first viewed Bennink’s work during an exhibition for the final examination at the Minerva Academy in Groningen. That was in 1999. I remember a concrete sculpture of a woman, robust and sturdy – but above all breath-taking. My interest in Bennink’s work was piqued.

What happened first

It was some time before I again heard anything about her. In 2004, she received a commission from the Catholic diocese of Groningen to create a monument to Titus Brandsma for the Saint Boniface Chapel in Dokkum. Brandsma, a Frisian Carmelite priest, resisted German occupation during the Second World War. He was consequently arrested and deported to Dachau, where he died from hardship. In 1985, he was beatified by the Roman Catholic Church. The sculpture that Bennink made of Brandsma is remarkably persuasive. She did not try to make a convincing and strong portrait of Brandsma, as others had done in their sculptures of him, but rather a much more supersensory, spiritual sculpture that builds a parallel with the suffering of Christ. The monumental work marks a caesura in her then still young career. In it, she not only shows her maturity as a sculptress but is also able to induce, in a cogent manner, a spiritual impact on the viewer. For her ultimate aim is to create sculptures with socially engaging content. Or as she once said herself, ‘[my] work consists primarily of life-size bronzes that use the human body as the bearer of meaning; the human being as allegory’.

In the years that followed, she continued to work hard at perfecting her work. A highpoint was the Venus of Kloosterveen (2007), created under commission to the City of Assen for the new Kloosterveen residential development. This larger-than-life sculpture, which embodies the strength, pride and vitality of the modern woman, again emphatically confirmed Bennink’s reputation as a sculptress.

The last five years: 2010-2015

Bennink’s work is monumental, powerful and, of course, figurative, as it is derived from observation of reality. At the same time, her work is far from being static and ‘dull’. Her phenomenal ability to shape clay enables her to compose sculptures comprising large abstract elements. More than anyone, she understands the art of reduction. She leaves out precisely those parts that others elaborate in detail. It is, in fact, this quality that makes Bennink’s sculptures so interesting: you, the viewer, are asked to complete the work and are therefore able to engage your imagination. As a sculptress, she bases her work on a clear concept that, in her case, defines the composition and anatomy of the final result. In this light, it is not surprising that she is involved in teaching, both as an instructor and coordinator of the sculpture department of the Classic Academy in Groningen.

Her collaboration with Bronsgieterij Ateliers MTW, a bronze foundry in Groningen, must certainly not be overlooked, as it plays a very important role in the ultimate production of her sculptures.

Portraits

Natasja has made many portraits; her subjects include well-known Dutch poet Rutger Kopland, football coach Gertjan Verbeek and painter Matthijs Röling. These are strong portraits that, more than anything, forefront their inner natures.

I saw her self-portrait ‘Koester de begeerte’ (Cherish the desire) at a solo exhibition at the Wildevuur Gallery in Hooghalen in 2014. The Drenthe Museum possesses a large collection of self-portraits of artists represented in its collection. The strikingly delicate portrait, with seductive eyes and naked breasts, aroused such an impression that arrangements were immediately made for its purchase. The power of this self-portrait is most emphatically located in tenderness, womanhood (the image can, in fact, be of everywoman) and vulnerable nakedness.

‘Onze koning’ (Our king; 2014) is created from an entirely different perspective. The competition for the portrait was organised by the Province of Drenthe. Bennink won the commission and produced a bronze portrait of Willem Alexander for the Provincial Council Chamber. It is a typical Bennink sculpture. A powerfully detailed head radiates authority and quietude above an elegantly abstracted chest. It is, in fact, a double portrait, as Bennink asked poet laureate for the Netherlands Anne Vegler to combine a poem with her creation (a brilliant idea!). The sculpture is nearly one and a half times larger than its subject in real life, allowing it to be viewed from all angles in the chamber.

Projects

The Venus series is an ode to women and constitutes a recurrent strand in Bennink’s work. The Venus of Kloosterveen (2007), the Venus of Drenthe (2010), the Venus of Ljouwert (2014), just to mention a few, have largely contributed to Bennink’s reputation. In fact, her previously mentioned final examination work was also a Venus variant. Venus is the Roman goddess of love; but far from the Roman Empire, small-scale sculptures were also made of “primal women” in celebration of fertility. The famous Venus of Willendorf from the late Stone Age is, for example, an idealisation of the feminine. Bennink’s Venuses are precisely intended to highlight the pride and self-awareness of women. She does not idealise at all. For example, the Venus of Drenthe (also in the collection of the Drenthe Museum and permanently displayed on the terrace) draws attention to its power and multifariousness from every sight line. The sculpture retains its strength and elegance when viewed from every angle. From the back, the musculature is deliberately accentuated in some places (girl power!), intensifying the excitement of the figure. The side view reveals, on the other hand, a sleek balanced line that runs from top to bottom (as shown in the study sketch), conveying an emphatically classic principle. Finally, the front view displays the woman in her full glory. Head proudly raised, hair braid flapping in the wind. The arms are firmly folded over each other, squeezing the breasts up and giving an extra accent to the beautifully rounded abdomen. She stands sturdily, feet apart, one foot turned out. This is an ode to all women in which Bennink’s hand (and therefore her individuality) is plainly visible in the bronze statue’s surface details. When casting, omission of clay results in elegant recessed areas, Natasja’s trademark, giving the surface a ‘rough’ appearance, as if still constructed from the original clay. In contrast, the feet are realistically formed. Precisely the tension between the abstraction and realism makes this work so special. The figure is mother and lover or, as Bennink once said: ’these days, women are both clichés and icons in a fast image culture, [but] my Venus sculptures are an ode to the woman of now and the future, readily recognisable by the contemporary individual’.

The erotic is a key element in some of her projects. Its basis is found in sensuality, love and physicality from the feminine perspective. The five statues comprising the ‘Ik en mijn minaar’ (I and my lover) project from 2012 display two lovers engrossed with each other. They could be anyone, for their faces betray no detail, being nearly scraped flat with a spatula during modelling. It seems as if Natasja wanted to capture tenderness in this series, but how in heaven’s name do you express such a feeling in three dimensions? And yet, she succeeds due to the sensuality that the works radiate, no matter how impossible that may seem. Her relationship with artist Onno Broeksma led to a decision by the artist couple to display their work in duo form as well, this in such exhibitions as the one in the Henriette Polak Museum in Zutphen. The products of their collaboration remind us of the Kamasutra, the famous Indian textbook on the art of love and seduction from the second century of the Christian era

De Vijf Kussen (The Five Kisses) of Appingedam (2013), five sculptures of Appingedam residents of all ages in the act of kissing, is a typical Bennink project. The aim was to use artwork to create a connection between the old city centre and a newer adjacent neighbourhood. Of course, Bennink chose people for this purpose: people from the city itself, a cross-section of residents from all levels of the population. And what was a better vehicle for this purpose than “the kiss”? After all, a kiss is a physical connection between people and stands, in the context of the commission, precisely for the requested intent. Such is the creative and intellectual power of Bennink; she knows how to place a rather abstract instruction into a human and social perspective. The process from commission to unveiling was also recorded by Marleen Gotlieb and became an extraordinary documentary that I saw at the Assen Film Festival This is also a characteristic of Bennink: record as must of the content-related and creative process as possible. The jury report includes the following remarks about The Five Kisses: ‘a kiss is universal and therefore accessible. The ordinary is not made extraordinary, not even by the manner of creation. Natasja Bennink includes a crude note in her work, which has something sturdy in it, banishing all slickness … ‘

Bennink wants to draw attention to social issues through her art. ‘I create sculptures in which I use a rough edge to reach people. Although art is not a requirement for life, I clearly see the necessity and beauty of sculpture.’

The latest project, on which she is still working at the time of writing, may be the most complicated to date. She entitled it ‘Quand on n’a que l’amour’. I saw the work, including the two models, in her studio in Ezinge. The models, intimately intertwined, were intensively observed by Bennink and with large almost savage interventions, she applied the finishing touches according to her personal vision. Both subjects of the portraits were noticeably impressed. Again, she knew how to flawlessly apply features to the sculpture that enable it to surpass even beauty.

Future

This book, From Kiss to King presents Bennink’s work from the last five years. A woman with a mission (2009) covers the preceding years, showing her work for the period of 1999 – 2009. Both publications are not traditional art books, which often display the work of an artist in a rather dry manner. Her collaboration with photographer Reyer Boxem is special, capturing her work in context at the moment that he perceives it. This creates interplay between sculpture and environment.

I am absolutely convinced that Natasja Bennink will make further large advances as a sculptress in the next five years. One development that is already perceivable (at least by me) will lead to even greater abstraction without abandoning mimesis. It will be in large, monumental sculptures that she will continue to excel in the future.